In a multiplayer session, game state information is communicated between multiple machines over an internet connection rather than residing solely on a single computer. This makes multiplayer programming inherently more complex than programming for a single-player game, as the process of sharing information between players is delicate and adds several extra steps. Unreal Engine features a robust networking framework that powers some of the world's most popular online games, helping to streamline this process. This page provides an overview of the concepts that drive multiplayer programming, and the tools for building network gameplay that are at your disposal.

If there is a possibility that your project might need multiplayer features at any time, you should build all of your gameplay with multiplayer in mind from the start of the project. If your team consistently implements the extra steps for creating multiplayer, the process of building gameplay will not be much more time-consuming compared with a single-player game. In the long run, your project will be easier for your team as a whole to debug and service. Meanwhile, any gameplay programmed for multiplayer in Unreal Engine will still work in single-player.

However, refactoring a codebase that you have already built without networking will require you to comb through your entire project and reprogram nearly every gameplay function. Team members will need to re-learn programming best practices that they may have taken for granted up to that point. You also will not be prepared for the technical bottlenecks that will be introduced by network speed and stability.

Introducing networking late in a project is resource-intensive and cumbersome compared with planning for it from the outset. We therefore advise that you should always program for multiplayer unless you are completely certain that your project will never need multiplayer features.

In a single-player or local multiplayer game, your game is run locally on a standalone game. Players connect input to a single computer and control everything on it directly, and everything in the game, including the Actors, the world, and the user interface for each player, exists on that local machine.

Single-player and local multiplayer take place on only one machine.

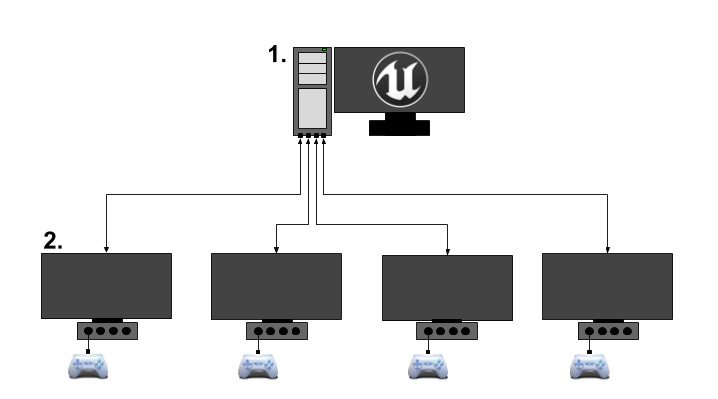

In a network multiplayer game, Unreal Engine uses a client-server model. One computer in the network acts as a server and hosts a session of a multiplayer game, while all of the other players' computers connect to the server as clients. The server then shares game state information with each connected client and provides a means for them to communicate with each other.

In network multiplayer, the game takes place between a server (1) and several clients (2) that are connected to it. The server processes gameplay, and the clients show the game to users.

The server, as the host of the game, holds the one true, authoritative game state. In other words, the server is where the multiplayer game is actually happening. The clients each remote-control Pawns that they own on the server, sending procedure calls to them in order to make them perform ingame actions. However, the server does not stream visuals directly to the clients' monitors. Instead, the server replicates information about the game state to each client, telling them what Actors should exist, how those Actors should behave, and what values different variables should have. Each client then uses this information to simulate a very close approximation of what is happening on the server.

For additional technical information about the connection process between clients and servers, refer to our guide on the Client-Server Model.

To help illustrate how this changes gameplay programming practices, we will use an example of two players in a multiplayer game. We will refer to them as Player 1 and Player 2, and break down the process of having them fire projectiles at each other.

| Local Gameplay | Network Gameplay |

|---|---|

| Player 1 presses an input to fire a weapon. |

Player 1's Pawn responds to this by firing its current weapon.

Player 1's weapon spawns a projectile and plays any accompanying sound or visual effects. | Player 1 presses an input on their local machine to fire a weapon.

Player 1's local Pawn relaying the command to fire the weapon to its counterpart Pawn on the server.

Player 1's weapon on the server spawns a projectile.

The server tells each connected client to create its own copy of Player 1's projectile.

Player 1's weapon on the server tells each client to play the sound and visual effects associated with firing the weapon. | | Player 1's projectile moves forward from the weapon. | Player 1's projectile on the server moves forward from the weapon.

The server tells each client to replicate the movement of Player 1's projectile as it happens, so their version of Player 1's projectile also moves. | | Player 1's projectile collides with Player 2's Pawn.

The collision triggers a function that destroys Player 1's projectile, causes damage to Player 2's Pawn, and plays any accompanying sound and visual effects.

Player 2 plays an onscreen effect as a response to being damaged. | Player 1's projectile on the server collides with Player 2's Pawn.

The collision triggers a function that destroys Player 1's projectile on the server.

The server automatically tells each client to destroy their copies of Player 1's projectile.

The collision triggers a function that tells all clients to play the accompanying sound and visual effects for the collision.

Player 2's Pawn on the server takes damage from the projectile's collision.

Player 2's Pawn on the server tells Player 2's Client to play onscreen effects as a response to being damaged. |

In the standalone game, all of these interactions take place in the same world on the same machine, so they are easy to both understand and program in literal terms. When you spawn an object, for instance, you can take for granted that all players will be able to see it.